Women and ethnic minorities remain underrepresented in science and in leadership positions across scientific organizations. Representation of women of color is even lower across the industry, academia, and federal workforces. Examining the views and experiences of those impacted and developing strategies to overcome this gap is a crucial step for any organization.

Stress can generally be defined as a change or shift that causes physical, emotional, or psychological tension.1 Although positive or negative, stress can ultimately result in physiological changes detrimental to one’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior. The effects of stress are further exacerbated in medical providers. Stress in the medical field has been a distressing theme, particularly since the emergence of the infamous phenomenon, “burnout.” Incorporated into the mental health lexicon in the 1970s by American psychologist Herbert Freudenberger, burnout is used to describe severe stress levels conceptualized in working professionals.2 Physicians and professionals alike commonly experience this exhaustive emotional state due to several factors, including the demanding nature of work and social expectations. Despite the positive impact clinicians have on society, the altruistic tradition of medicine, which places the welfare of society above self-interest, can oftentimes result in the decline of the provider, compromising the overall quality of care.

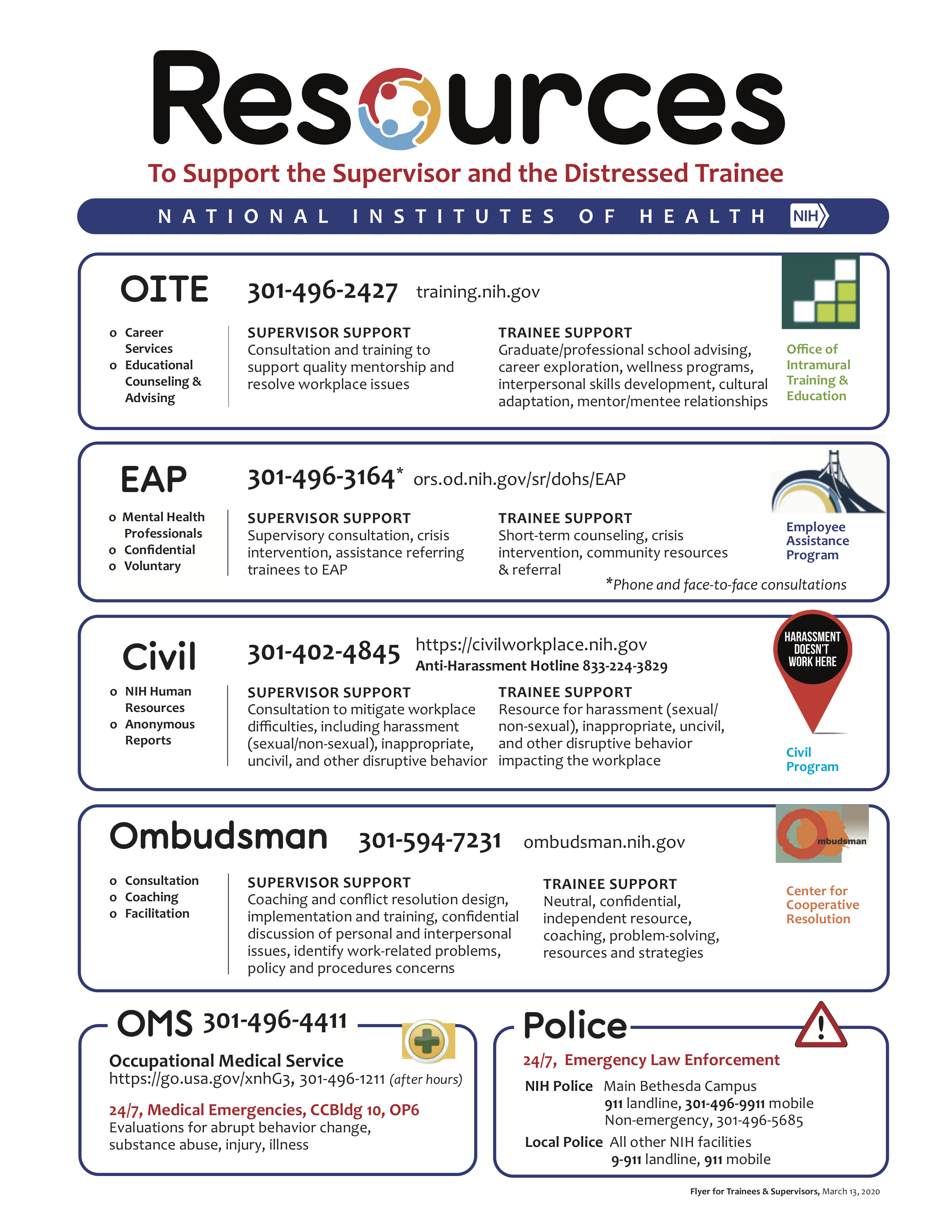

To address this obstacle, there are several distinct resources available to NIH clinicians, including but not limited to the NIH’s Employee Assistance Program (EAP). This confidential resource provides NIH employees with access to professional counseling services, such as crisis intervention and support for personal growth and development. The EAP also teaches skills for managing stress, including stress assessment and awareness, time management, and relaxation exercises.3 Endorsed by the American Psychological Association, other evidence-based methods of alleviating stress include progressive muscle relaxation, meditation, sleep, and social support.4 Through these practices, one can reduce stress levels and develop resiliency.

According to Dr. Sharon Milgram, Director of the Office of Intramural Training & Education at NIH, those who are resilient prepare to be resilient, as it requires self-reflection, learned experiences, and practice. Through the development and utilization of individualized stress management skills, clinicians and other professionals can learn to “bounce back” from difficult situations and ultimately achieve profound personal growth—positively transforming the quality of care to a more proficient medical practice.

1 Scott, E. (2020, August 3). What is Stress? Retrieved March 06, 2021, from https://www.verywellmind.com/stress-and-health-3145086

2 InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Depression: What is burnout? [Updated 2020 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279286/

3 Employee Assistance Program (EAP), Division of Occupational Health and Safety, National Institutes of Health Office of Management. (2021). Retrieved March 06, 2021, from https://www.ors.od.nih.gov/sr/dohs/HealthAndWellness/EAP/Pages/index.aspx

4 Healthy ways to handle life's stressors. (2019, November 1). Retrieved March 06, 2021, from https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/tips

Master Stress transcript

M aintain healthy eating

A void social isolation

S tay informed, not obsessed

T alk to others

E ngage in mindfulness

R elax, play, exercise

S tart journaling

T ake deep breaths

R est and sleep well

E ngage in gratitude

S tep outside into nature

S eek support from friends, family, and professionals

Resources to Support the Supervisor and the Distressed Trainee